By : Prof. Dennis B. McGilvray

Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA

from South Asian History and Culture

This article explores the influence of local concepts of matrilineal kinship and descent through women in the construction of a modern Sufi silsila (an authorized ‘chain’ of spiritual and genealogical ancestry) in Sri Lanka. Makkattar Vappa, a popular Sufi shaykh in the Tamil-speaking eastern region of the island, asserts hereditary maulana (sayyid) status as a member of the Prophet’s household descent group (ahlul bayt) by means of close genealogical linkages to a locally enshrined saint of Yemeni family ancestry traced through several women, including his mother, his father’s mother, and his wife. The kinship system here is Dravidian in structure, but with a matrilineal emphasis that is seen today in the administration of Hindu temples and Muslim mosques by matrilineal clan elders, and in the negotiation of matrilocal marriages based upon women’s pre-mortem acquisition of dowry property in the form of houses and paddy lands. The shaykh in question is himself the successor Kālifā of a Sufi order (tāriqā) based in Androth Island, Lakshadweep, a similarly matrilineal society located off the west coast of India. In his prior career, he was an art and drama teacher in a local government school, and his style of Sufi leadership continues to be pastoral and pedagogical in tone. This, together with a strong base of support from former students, has enabled him to escape the sort of stridently anti-Sufi violence that has erupted in Muslim communities elsewhere in the region. His awareness of anthropological research on matrilineal kinship and marriage patterns in this part of the island may have encouraged him to trace his sayyid silsila through both male and female genea-logical connections.

Keywords: Sufi; sayyid; religion; kinship; Sri Lanka

Muslim matriliny in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s Muslims or ‘Moors’, 9% of the total population and overwhelmingly Sunni and Shafi’i in Islamic heritage, make up roughly 50% of the Tamil-speaking population in the Eastern Province of the island, a region comprising three coastal districts: Trincomalee, Batticaloa, and Amparai. In the latter district, where sea fishing and paddy farming are the foundations of the local economy, they outnumber the Tamil Hindus and Christians as well as the Sinhalese Buddhists. Throughout the island, the Sri Lankan Muslims or Moors have been historically and culturally linked with the coastal Marakkāyar Muslims of Tamil Nadu and the Māppiḷa Muslims of northern Kerala, a shared heritage from centuries of maritime trade between the Middle East and South Asia. 1 The term ‘Moor’ is an anglicized colonial usage derived from the Portuguese mouro (people of Morocco or the Mahgreb), the label applied to all Muslims in the Portuguese colonial lexicon. Today the more common term is simply ‘Muslim’, but the older term Moor, and its Tamil equivalent (cōṉakar), more accurately distinguishes the ethnicity of the community as Tamil-speaking Sri Lankan Sunni Muslims who follow the Shafi’i school of Islamic law. In the latter respect, they share their south Arabian Shafi’i legal heritage with coastal Muslim communities throughout southern India and Southeast Asia. (2)The ethnic designation of Moor or cōṉakar also serves to distinguish them from other, much smaller Sri Lankan communities that profess Islam: Malays, Bohras, Khojas, and Memons.

The medieval Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms of Kerala and Sri Lanka allowed Arab merchants – many of whom acquired local wives by whom they fathered Indo-Muslim progeny – to dominate pre-colonial trade in port settlements such as Calicut and Colombo. (3) Soon after Vasco da Gama’s 1498 hostile naval encounter with the ‘Moors’ of Calicut, the Portuguese encountered Muslim traders in Ceylon who spoke Tamil and who had been given royal permission to collect customs duties and regulate shipping in the major southwestern port settlements under the suzerainty of the local Sinhalese Kings of Kotte. (4) Commercial, cultural, and even migrational links between Muslim towns in southern India and Sri Lankan Moorish settlements are confirmed in the historical traditions of Beruwala, Kalpitiya, Jaffna, and other coastal settlements where Sri Lankan Muslims have lived for centuries. (5) In a reciprocal gesture, many Sri Lankan Moorish families have longstanding devotional attachments to Sufi tomb-shrines located along the Tamil Nadu coastline, or are followers of contemporary saintly shaykhs and tangal sayyids from Kerala and the Lakshadweep Archipelago.

According to colonial eyewitness accounts between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, (6) Tamil-speaking Muslims were already well established as farmers, fishermen, and merchants living in enclaved villages on the east coast under the political domination of hereditary matrilineal Tamil Hindu chiefs and landlords of the Mukkuvar caste, a group who appear to have seized control of the region as mercenary soldiers and sailors from the invading south Indian army of Kalinga Magha in 1215 C.E. (7) Tamil Mukkuvar chiefs in Batticaloa and Amparai districts have long proclaimed their kingly warrior heritage in the oral traditions and ethno-historical chronicles of the east coast, but a maritime caste of the same name is also found today in coastal Kerala, a region anthropologically famed for its matrilineal family patterns.(8)

The (canonically) seven Mukkuvar chiefdoms encountered in the Batticaloa region by the Portuguese (1505–1658) and the Dutch (1658–1796) were strongly infused with a matrilineal ideology of political succession and landholding, and they supported a society-wide kinship structure in all castes based upon hierarchically ranked exogamous matrili-neal descent groups (matriclans), referred to in Tamil as kuṭi. The presumptive origin of matrilineal politics, land tenure, and family organization among both the Tamils and the Moors is the historic ‘Kerala connection’ of the Mukkuvars, as well as the intermarriage of Muslim men with local matrilineal Tamil Hindu women. Circumstantial evidence for this can be seen in a number of Moorish matriclan names that are strikingly similar to those of their Tamil neighbours. (9) Under the British colonial administration that took control in 1796, and following Sri Lankan independence in 1948, the economic and political influence of the Mukkuvar chiefs and landlords (pōṭiyār) steadily weakened, giving the Moors an opening to acquire paddy land and free themselves from semi-feudal subordination to the Tamils.

Today, in the wake of the 2009 defeat of the LTTE – and despite the disproportio-nately devastating impact of the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 upon the Muslim com-munity (10) – the Muslims today are visibly the most prosperous community on the east coast, and their educational achievements have caught up to those of the Tamils, who initially benefited from nineteenth-century Christian missionary schooling.

Today, in the coastal farming town of Akkaraipattu in Amparai District – with its population of about 65,000 – where I have based most of my ethnographic fieldwork, the matrilineal principle is still seen in the administrative structure of the oldest Hindu temples and Muslim mosques, which are run by committees composed of male trustees (Hindu vaṇṇakkar, Muslim maraikkār) of the leading matriclans in the congregation. On the Hindu side, these matriclans (and also lower-ranking service castes) continue to sponsor ‘shares’ of the annual week-long puja festivals for the temple deities, thus ceremonially exercising their hereditary rights and dramatizing their hierarchical status for all to see. On the Muslim side, I collected oral accounts of a now-defunct tradition of matriclan sponsorship of annual kandoori (kantūri, equivalent to north Indian urs) festivals on the death anniversaries of Sufi saints enshrined in tomb-shrines (ziyāram, equivalent to Indian dargah) at local mosques. There was a time, reportedly lasting up until the 1960s, when the matrilineal mosque trustees also meted out corporal punishment by caning Moorish miscreants and instructed Moorish voters on how to cast their ballots in local and national elections. Since then, however, the mosque trustees have been chastened by their unsuc-cessful efforts to dictate local politics, which are nowadays controlled by local ‘big men’ backed by national political parties.

The so-called Mukkuvar Law, an ancestral matrilineal property system in the Batticaloa region, was peremptorily invalidated by the British in 1876, and most of what we know of its prior application is contained in a short and frustratingly obtuse treatise on the subject by a Ceylon Burgher attorney, Christopher Brito, published in 1876. (11) Despite the temptation of some legal historians to view the Mukkuvar Law as based upon the strictly matrilineal Marumakkattayam Law historically followed by the Nayar caste of central Kerala, (12) the actual operation of the Mukkuvar Law seems to have featured a complex mixture of both matrilineal and bilateral inheritance. When the colonial government chose to discontinue the Mukkuvar Law in the civil courts after 1876, there appear to have been relatively few complaints from the Tamils in the Batticaloa region where it had been applied. The most plausible hypothesis is that, by then, most family property was already being passed to daughters in the form of dowry at marriage, rather than as post-mortem inheritance from parents. For both Tamils and Moors today the intergenerational transfer of real property – houses and paddy lands – is still overwhelmingly from parents to their daughters in the form of dowry (cītaṉam) at marriage, or as an outright gift (naṉkoṭai) to their daughters prior to marriage. The residence pattern itself is matrilocal at the outset, with the son-in-law moving into the house occupied by his wife and her parents and her unmarried siblings for the early years of marriage. When the time comes for a younger daughter to be married, her parents will – if possible – shift into a new dowry house they have built for her nearby, leaving the older married daughter and son-in-law in the older house as an independent nuclear family unit. (13)

For Hindu and Christian Tamil families, the preference is to sign a so-called ‘dowry deed’ (cītaṉam uṟuti) that legally gives joint undivided ownership of the house and land to the daughter and son-in-law. In contrast, Moorish parents are more likely nowadays to bestow outright ownership of family property as a gift to their daughters prior to marriage, sometimes even in childhood. This is said to avoid troublesome property litigation in the case of a divorce, and it responds to the complaints of Islamic reformists who object to recognizing the ‘Hindu’ practice of dowry as a part of modern Sri Lankan Muslim marriage. Surprisingly, in the context of global Islamic fundamentalism and purification of the faith, this ends up reinforcing, rather than weakening, Sri Lankan Muslim women’s traditional property rights, since the preference for matrilocal dowry-house-based families remains unquestioned. The post-mortem inheritance of Moorish family property is always governed by Sri Lanka’s version of sharia law, which is primarily Shafi’i in practice. In most cases, however, there is very little property left to inherit after all the daughters (and sometimes the mother’s sororal nieces) have been provided for by ‘pre-mortem’ gifting. This presumes, of course, that a bride’s parents have the wealth necessary to offer a dowry house in the first place. Poor or dispossessed women have difficulty finding a husband, unless they are lucky enough to secure an independent love match. Such women, or their mothers, have been known to work as housemaids in the Middle East in order to construct the essential dowry houses needed for marriage in Sri Lanka. (14)

Because of this pervasive dowry-based system of property transfer to women – either as sole owners or as co-parceners with their husbands – the destruction caused by the 2004 tsunami posed a significant loss to the long-term household estates of many women, both Tamil and Moorish. Relief aid in the aftermath of the tsunami was often extended to men – husbands, fathers, brothers, sons – who were assumed to be the responsible ‘heads of households,’ rather than to the women who had been the legal proprietors. While this raised alarm bells among local women-centred NGOs, it has proven to be only a temporary problem, because most externally provided post-tsunami housing is destined to be passed again to women as dowry property when younger daughters reach marriage-able age. (15)

Not surprisingly, however, the strength of matrilineal clan (kuṭi) identities appears to be gradually weakening in the twenty-first century along with the taboo on marriages within the clan, especially among younger Tamils and Moors for whom the old-fashioned ritual status (or stigma) of matriclan ranking affords less and less meaning or benefit. Still, because of the Dravidian-type kinship terminology shared by the Tamils and the Moors, it remains awkward to marry someone who is a member of your very own matriclan without at least a slight connotation of committing classificatory incest. Among Tamils and Moors of the senior generation, an awareness of matriclan identity, and of ancestral marriage alliances between specific matriclans, is still nostalgically preserved.

In sum therefore, the principal components of Muslim ‘matrilineality’ in eastern Sri Lanka are historically sanctioned administration of major temples and mosques by committees of matrilineal male clan elders; matrilocal post-marital residence, and transfer of family houses and paddy lands to daughters at, or sometimes prior to, marriage; and awareness, especially among older residents, of distinct matrilineal des-cent-group identities and rules of exogamy, including longstanding trans-generational marriage exchange alliances between specific matriclans, each with its own symbolic marks of social prestige.

Makkattar Vappa: a contemporary Sri Lankan Sufi shaykh

I have discussed elsewhere (16) the outbreak of violence directed against charismatic Sufi shaykhs in the densely populated Muslim town of Kattankudy in Batticaloa District, a problem attributed to the rise of staunchly reformist – some would say Salafist or Wahhabi or Towheed – groups who are hostile to all Sri Lankan Muslim traditions of saint veneration and Sufi mysticism. This is only one of the many global pan-Islamic influences that have been felt in Sri Lanka’s Muslim community. Earnest, bearded, white-robed, door-to-door missionary teams from the Tablighi Jamaat are nowadays a familiar sight in Muslim neighbourhoods, urging lapsed worshippers to resume their daily prayers. Evening and weekend study-groups organized by the Jamaat-i-Islami are aimed at a more educated middle-class Muslim audience who desire a deeper and more detailed understanding of the Quran and Hadiths. (17) Increasingly, nowadays, one also finds inde-pendent mosques loosely labelled Towheed (tawhid, the unity and alterity of Allah) congregations that are widely alleged to receive funding from missionary ‘Salafist’ or ‘Wahhabi’ organizations abroad. Today Sri Lankan Muslims seeking to maintain their older, traditional religious practices feel obliged to identify themselves as sunnattu jamaat, members of the ‘customary or standard’ community of Muslims.

The primary targets of Sri Lankan Muslim reformist groups are the older traditions and institutions of Sri Lankan popular Islam, such as vow-making at the tombs of Sufi shaykhs and Maulana seyyids, and the celebration of the annual saints’ festivals that women and children still so often attend and enjoy. These festivals may feature public exhibitions of ecstatic, self-mortifying Sufi devotional practice (zikr) by Bawa faqirs of the Rifai order, unchanged in over half a century. (18) When any of these events attracts an audience of non-Muslims, especially Hindus, it is taken as evidence that something ‘non-Islamic’ must be happening. For example, the popular Sufi pilgrimage shrine at Daftar Jailani in the Kandyan Hills has frequently generated complaints from Islamic reformist groups, although it lacks a tomb for saint Abdul Qadir Gilani (1077–1166 CE, buried in Baghdad) whose astral visit is celebrated there. Most recently, starting in 2013, the Daftar Jailani shrine has also been the target of militant anti-Muslim Sinhala Buddhist monks, such as the Bodu Bala Sena (‘Buddhist Strength Force’), who seek to reassert control over it as an ancient Buddhist archaeological site. (19)

As the professionalization of the Islamic clergy has steadily increased through higher levels of seminary training, the regional and national councils of the Ulama have exerted greater theological control, including the issuance of fatwas (legal interpretations) to scold or to excommunicate particular heterodox Sufi shaykhs for their alleged pantheism or deviant interpretations of Islamic theology. In Kattankudy, a densely populated Muslim town near Batticaloa with historic commercial ties to South India, a controversial Sufi leader named Rauf Maulavi established his own mosque adjacent to the ziyaram (tomb-shrine) of his father several decades ago and developed a well-funded organization (All Ceylon Islamic Spiritual Movement) to disseminate his books and newsletters in Tamil. Because he espoused the allegedly ‘pantheistic’ doctrines of the twelfth-century Sufi philosopher Ibn Arabi (wahdat-ul-wujūd, or ‘unity of creation’), his teachings were condemned by fundamentalist opponents as a violation of tawhid, the radical unity and alterity of Allah, and he was declared an apostate (murtad) in a fatwa issued by the All Ceylon Jamiyathul Ulama in 1979. Despite ostracism and periodic attacks on his property, Rauf successfully defied the fatwa for decades, backed up by his own muscular and well-financed group of local followers, and ultimately the decree was rescinded. He was driven from Kattankudy by mob violence in late 2006, and he is now based in Colombo. However, he retains a strong core of supporters and disciples, and he maintains an active website in the name of his saintly father, Al Haj Abdul Jawadh ( http://www.ajawt.org).

The headquarters shrine of a second Sufi leader, the late Shaykh Abdullah Payilvan, was also attacked in December 2006 at the same time that Rauf was expelled, in a convulsion of mob violence sparked by the burial of Payilvan’s body in a private tomb at his shrine near the seaside in Kattankudy. The followers of Payilvan belong to a new Sufi order he founded called Thareekatul Mufliheen, and they actively distribute a wide array of Payilvan’s published books and recorded songs on their website ( www.mufliheen.com). Payilvan, like Rauf, had been declared an apostate for his pantheistic theology, and his corpse was barred from burial within the boundaries of Kattankudy (a totally Muslim town) by conservative Muslims. Rumours also circulated that Payilvan’s followers had filled his tomb with honey, an idolatrous gesture anathema to Islamic reformist sensibil-ities. As a result, mobs tore down the Mufliheen headquarters shrine and its imposing minaret, removed Payilvan’s corpse from his tomb, and took it to a hidden location where it was reportedly burned. Even Sri Lankan Muslims with no sympathy for Payilvan’s Sufi doctrines have found this desecration and cremation of his body to be appalling, with its symbolic implication that Payilvan was in fact a Hindu. The website maintained by the Thareekatul Mufliheen includes an archive of over 20 years of legal appeals and diligent civil rights injunctions lodged on behalf of Payilvan, along with photos of the 2006 violence. His followers have by now rebuilt most of his shrine and have also obtained a permanent Sri Lankan Police guardhouse for the premises.

For reasons that are not entirely clear, this sort of violent opposition to Sufi shaykhs and their devotional followers has not yet arisen in Akkaraipattu, located only 75 km south of volatile Kattankudy on the east coast road. (20) From the 1970s – and possibly earlier – several groups of Sufi-oriented Muslim laypeople have met for Thursday evening zikr (devotional practice) at private residences in Akkaraipattu, including a branch of the Tamil-speaking ‘Sufi Manzil’ organization originally founded in Kayalpattinam, Tamil Nadu, in 1975 with chapters in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Sri Lanka. (21) This organization also espouses the encompassing ‘unity of creation’ (wahdat-ul-wujūd) philosophy of Ibn Arabi, one of the theological issues that generated hostile anti-Sufi violence in Kattankudy. The Sufi shaykh described in this article, however, is locally rooted in Akkaraipattu, where he grew up and served for much of his life as an elementary school art instructor.

Born A.S.A. Abdul Majeed Makkattar, and popularly known for most of his life as ‘Makkattar Majeed’, he was a popular teacher known for his artistic creativity in the classroom and in staging dramatic productions with his students. Among his many grade school alumni and spiritual supporters is the local Member of Parliament, a cabinet minister (2001–present) in the government of President Mahinda Rajapakse, (22) who has provided ample patronage to his voter base in Akkaraipattu, including major road projects and a new municipal water supply. With such an influential ally on his side, Makkattar has enjoyed at least short-term insurance against any local anti-Sufi detractors. The only organization that might pose a formal threat in Akkaraipattu is a reformist tawhid mosque that calls itself the Centre for Call and Guidance (in Tamil, vaḻikkāṭṭu nilaiyam), headed by a sincere and resolute young Maulavi who told me he had become disillusioned with the Tablighi Jamaat after spending several years working with them in Pakistan and Bangladesh. (23) Although I did not learn the details, the clear implication was that his current theology was located to the right of the Tablighi Jamaat. His adherents are said to be growing among the poorer Moors who live on the periphery of the town.

In the mid-1970s, Makkattar encountered a visiting Sufi shaykh from Androth Island in the Lakshadweep archipelago, a Union Territory of India in the Arabian Sea to the west of Calicut, Kerala. Although it has not been noted in the scholarly literature, there has been a significant stream of Sufi shaykhs (often bearing the title of tangal, the Malayalam equivalent of maulana) travelling on circuit from Androth Island to Sri Lanka and back starting in the nineteenth century or possibly earlier. Today a tangal from Androth runs the Sri Lankan office of the Rifai Sufi order near the Grand Mosque in Colombo’s Pettah district, and it is through the teaching of Androth and northern Kerala based shaykhs that the musical tradition of the rifai ratib, a devotional Sufi call and response performance genre, was spread to Sri Lanka.

The full title of the Androth shaykh to whom Makkattar became attached was Qutbul Aktab Hallajul Mansoor, but he was popularly called Maulana Vappa (‘Father Maulana’) in keeping with his maulana (sayyid) lineage and his role as a spiritual father to his disciples, whom he regarded as his ‘children’ (piḷḷaikaḷ). Over the course of several years and multiple visits to Akkaraipattu and to other places in Sri Lanka, he is said to have miraculously cured Makkattar of a life-threatening kidney disease. Makkattar eventually became Hallaj Mansoor’s chief Sufi disciple (murīd) and his designated Sri Lankan

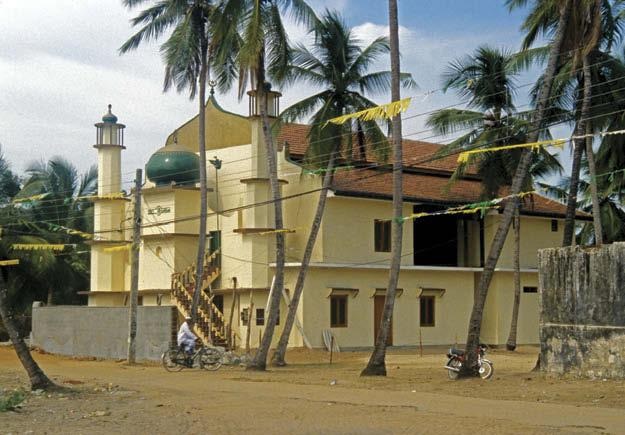

Figure 1. (Colour online) Hallaj Mosque, Akkaraipattu, Sri Lanka.

deputy when he was away in Androth. Leading a congregation of fellow Sufi initiates, Makkattar raised funds and built a private mosque to conduct zikr as taught by Hallaj Mansoor in Akkaraipattu, including a special room for the Androth shaykh to stay in when visiting and – it was hoped – to be buried in when he died ( Figure 1). As it turned out, Hallaj Mansoor expired in 2005 and was entombed on his home island of Androth, but not before officially designating Makkattar as his successor kālifā to lead his entire tāriqā or spiritual lineage worldwide, which he identified as ‘Qadiriyyi Chishti’. (24) During one of the Androth shaykh’s tours of Sri Lanka in 2001, I was handed a cellphone by Makkattar who had dialed up Hallaj Mansoor in Puttalam on the opposite side of the island. It was not easy to have a spontaneous dialogue in Tamil over a crackly mobile connection with a mumbling holy man whom I had never met, but afterward I basked in the awe of Makkattar’s Sufi acolytes. My conversation was regarded as verbal darshan, or barakat by cellphone!

Since assuming the black mantle, or khirka, of kālifā-hood, the Akkaraipattu shaykh has begun to refer to himself in print as al-Qutub as-Shaykh as-Sayyid Kalifatul Hallaj Abdul Majeed Makkattar, but in person he prefers people to address him as ‘Father Makkattar’ (makkattār vāppā) in the paternal fashion of his predeces-sor. With the intimacy of a parent at home, he transfers rice and curry directly from his own plate onto the plates of his ‘children’ and mixes their food with his own hand. Similarly, in official photographs he poses in ornate robes and rosary beads and a pleated turban bedecked with medallions like an Indian state guard of honour, but in his sandy yard at home he can usually be found wearing a worn short-sleeved shirt and a simple cotton handloom sarong, rocking on a child’s plank swing hung from the low-hanging branch of a mango tree, smoking endless cigarettes, and constantly answering his cellphone in the company of a hovering cluster of younger male followers.

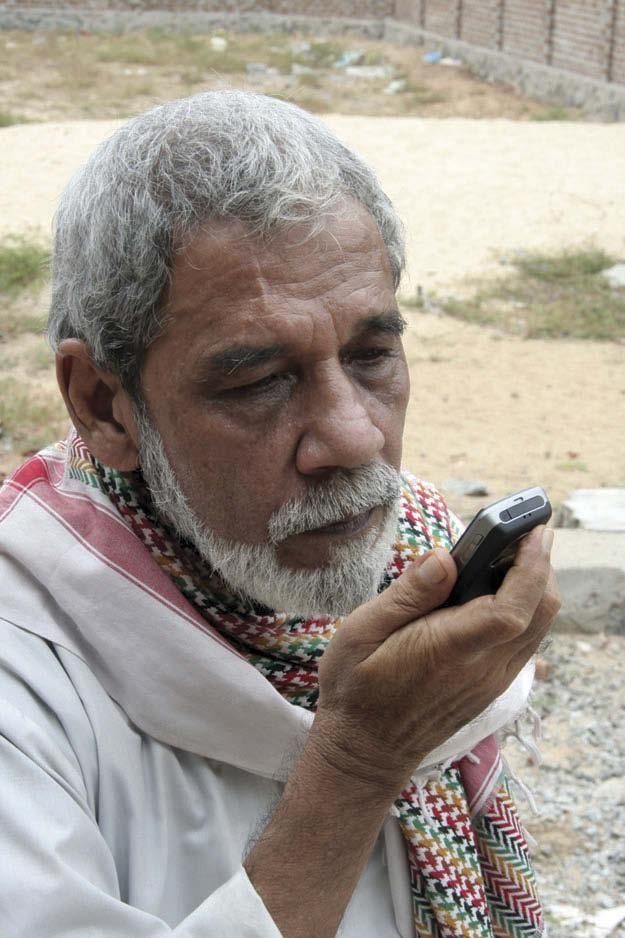

On every occasion I have met with Makkattar since 2002, he has displayed a newer model cellphone, each a gift from one of his disciples who is eager to receive the outdated model charged with the spiritual power (barakat) it has acquired through the constant traffic of Makkattar’s healing words. Equipped with the latest mobile technology, Makkattar receives calls from followers in Dubai, Denmark, and New Zealand I was told, and he often uses his cellphone as a long-distance curing instrument. A remote patient is instructed to hold the receiver against the afflicted part of his or her body while Makkattar transmits curative blessings through his cellphone ( Figure 2). He also counsels troubled women privately and draws pastel portraits of his deceased shaykh Hallaj Mansoor, practices that could readily attract the disapproval of fundamentalist critics ( Figure 3). People often drop by without appointments, and Makkattar offers them a combination of pastoral advice,

Figure 2. (Colour online) Makkattar using cellphone to transmit curative blessings.

Figure 3. (Colour online) Makkattar holding personal portrait of his late Sufi master, Shaykh Hallaj Mansoor.

protective talismans, and erudite philosophical lectures, depending upon the situation. His gravely, tobacco-stressed voice never seems to wear out.

Saintly connections through women

My initial grasp of Makkattar’s philosophy and personal background was derived from rambling conversations and meals with him while visiting Sri Lanka periodically over several decades. (25) However, in 2010 he gave me a 270-page compendium of his writings in Tamil entitled Hallājiṉ Pōtaṉaikaḷ (‘Teachings of Hallaj’) in which he explores topics ranging from the astronomical calculation of Islamic prayer times and the pros and cons of Ibn Arabi’s doctrine of Wahdat-ul-Wujūd, to the alternative ways of tracing spiritual connections back to the Prophet Muhammad and the detailed history of his own spiritual and genealogical lineage or ‘chain’ (silsila). His initiation as a disciple of the Androth shaykh and his eventual designation as spiritual successor to lead the shaykh’s Sufi order are documented in the book in multiple ways, both textually and photographically. (26) However, the book also seeks to validate Makkattar’s sayyid family ancestry going back to the Prophet Muhammad, a connection that rests crucially upon his recent genealogical tree.

Practically speaking, the crucial test of Makkattar’s identity as a hereditary member of the ‘house of the Prophet’ (ahlul bayt) is to be found not in the most distant links of his genealogy but in the preceding three generations of his family in Akkaraipattu who were descended from a well-known Yemeni (Zabidi) sayyid merchant, Shaykh Ismail, who migrated to Dutch Ceylon in the mid eighteenth century. (27) Shaykh Ismail is known to have fathered 11 sons by three different wives, and their tombs are to be found scattered in many parts of the island today, including the ziyāram of the youngest son of Ismail’s third wife located on the premises of the second-oldest mosque in Akkaraipattu (Siṉṉappaḷḷi, also referred to as ‘Town Mosque’). Oral tradition says that Shaykh Ismail originally stepped ashore near Akkaraipattu having floated in ‘on a plank’ from Yemen, so the return of his youngest son, Shaykh Abdussamat Maulana, to settle in the town was a source of local pride. Abdussamat’s first wife was from Dikwela in the southern coastal region near Galle, but his children from that early marriage are seldom mentioned. When he moved to Akkaraipattu he took two additional wives, the first from the nearby town of Pottuvil and the second from Akkaraipattu itself. Makkattar is a grandson of Abdussamat Maulana by both of these marriages, and his late wife Ayisha was a great-great-granddaughter of the saint as well ( Figure 4).

However, none of Makkattar’s ancestral connections with Abdussamat Maulana can be traced exclusively through males, as would be expected for sayyids throughout most of the Muslim world, and especially for the descendants of a Yemeni holy man. In each of these genealogical paths there is at least one female link. His late mother was Abdussamat’s granddaughter by the Pottuvil wife. His father’s mother was Abdussamat’s daughter by the Akkaraipattu wife. Makkattar’s own late spouse Ayisha – whom he explicitly honours as a female sayyid – traced her descent from Abdussamat and his Akkaraipattu wife entirely through three generations of women. Makkattar’s son married a non-maulana bride, but their children can claim conventional patrilineal sayyid membership as long as Makkattar’s own sayyid credentials are validated. Makkattar’s daughter, on the other hand, married his sister’s son. This is a perfectly correct Dravidian cross-cousin marriage, but one that will add two more female links to the future sayyid silsila of their children.

The logic of Makkattar’s silsila is not strictly speaking matrilineal, which would require an exclusively unbroken line of descent through women. Rather, he recognizes the genealogical transmission of sayyid identity through both male and female ancestors, which in kinship jargon would qualify as a pattern of ‘bilateral descent’. However, his openness to matrilineal possibilities is seen in the silsila of his late wife, Ayisha, whose sayyid qualifications were preserved entirely through three intermediate generations of women descended from Abdussamat Maulana.

The overlapping kinship connections between Makkattar and his saintly grandfather Abdussamat Maulana have been echoed in his close physical propinquity to the saint throughout his life ( Figure 5). He was born in his mother’s house located only two blocks away from the Town Mosque containing the saint’s ziyāram. He married matrilocally into

Figure 5. (Colour online) Makkattar at tomb of Abdussamat Maulana.

Figure 6. (Colour online) Enshrined tombs of wife and mother, under construction.

his wife’s home situated diagonally across the street from the tomb-shrine, and his current residence is located just around the corner from it.

In recent years, Makkattar has undertaken construction of a large new multi-storied seaside Sufi retreat centre in Akkaraipattu with accommodations for visiting devotees, madrasa instructional classrooms, space for prayer and performance of zikr, and a built-in ziyāram (tomb-shrine) containing the side-by-side graves of his mother and his wife, still under construction in 2012 ( Figure 6). The zikr and prayer spaces (referred to as Zāviyatul Hallājiya) are named after Makkattar’s own shaykh and predecessor, Hallaj Mansoor. The instructional quarters (referred to as Matrasatul Āyishā) are named after Makkattar’s late wife Ayisha. A physical structure of comparable scale would be the headquarters shrine of the late Shaykh Abdullah Payilvan in Kattankudy, referred to earlier, which was attacked and desecrated by a fundamentalist mob in 2006. (28)

Questions and possibilities

The adjustment of Islamic property and inheritance rules, as well as Muslim marriage and domestic arrangements, to accommodate matrilineal social structures has been noted ethnographically in various parts of the world including south India and Malaysia. (29) The female dowry property, matrilocal marriage, and matrilineal mosque traditions I have documented among Moors in eastern Sri Lanka would belong in this category as well. However, I am now eager to determine if there are any historical precedents, ethnographic examples, or legal debates in the Islamic religious traditions of South Asia

– or of any other parts of the Muslim world for that matter – concerning the transmission of sayyid status to women, and especially to the offspring of such women. Obviously, the historical and ethnographic literature on Kerala and Lakshadweep, as well as Sumatra (Minangkabau), deserves a second look with these questions in mind. (30)

Does this Sri Lankan Sufi shaykh have a credible case for tracing the genealogical charisma of the Prophet through both male and female sayyid descendants? He clearly has an interest in doing so, because without it he cannot trace a conventional patrilineal link to the local saint buried in the Town Mosque, despite the existence of a great many close family connections. In any case, it should be noted that social and political organization throughout eastern Sri Lanka is historically matrilineal, and that Makkattar’s own family has played a leading role in the matrilineal clan administration of the Town Mosque. In a telling anthropological reversal, he pointed out to me in a 2012 interview that my own ethnographic research had shown matrilineal descent (tāy vaḻi, ‘mother way’) to be the foundational principle of kinship and descent in eastern Sri Lanka.

Quite possibly, too, he is inspired by a universalist belief in the spiritual equality of the sexes as exemplified by the Prophet’s own daughter, and by the saintly virtues of his own wife and mother. In a conversation with Makkattar in November 2010, I remarked that all of the ‘people of the house’ of the Prophet Muhammad were uniquely connected through his only surviving child, his revered daughter Fatima Zahra.

He smiled and nodded approvingly.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research fellowships from the American Institute of Sri Lankan Studies (AISLS) and from the American Institute for Indian Studies (AIIS). For his essential role in this research, I wish to thank first of all Al-Qutub As-Shaykh As-Sayyid Kalifatul Hallaj Abdul Majeed Makkattar. I also gratefully acknowledge the research assistance provided by Nilam Hamead and family, as well as the support of M.A. Phakurdeen, K.M. Najumudeen, K. Kanthanathan, and many other Moorish and Tamil friends in Akkaraipattu.

Notes

- See McGilvray, “Arabs, Moors, and Muslims.”

- See Fanselow, “Muslim Society in Tamil Nadu.”

- See Arasaratnam, Ceylon; Dale, The Māppiḷas of Malabar; and Kiribamune, “Muslims and the Trade of the Arabian Sea.”

- See Ameer Ali, “Some Aspects of Religio-Economic Precepts and Practices in Islam”; Indrapala, “Role of Peninsular Indian Muslim Trading Communities”; and Abeyasinghe, “Muslims in Sri Lanka in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.”

- See Casie Chitty, The Ceyon Gazeteer; Denham, Ceylon at the Census of 1911; and Ameer Ali, “Genesis of the Muslim Community in Ceylon.”

- See Neville, “The Nâdu Kâdu Record”; de Graeuwe, Memorie; and Burnand, Memorial.

- McGilvray, Crucible of Conflict, ch. 2.

-

Not all Mukkuvar caste communities in south India are matrilineal. See Ram, Mukkuvar Women, for an excellent account of the non-matrilineal Mukkuvar fishers of Kanya Kumari district, Tamil Nadu. Similarly, Mukkuvar fishermen in the Jaffna peninsula of Sri Lanka are not matrilineal.

- See McGilvray, Crucible of Conflict, ch. 8.

-

See McGilvray and Rahim, Muslim Perspectives on the Sri Lankan Conflict; and McGilvray and Gamburd, Tsunami Recovery in Sri Lanka. The experience of the Eelam Wars (1983–2009) was highly traumatic for the Moors in the eastern and the northern parts of the island. In 1990 the Muslims of Jaffna and Mannar were expelled from their homes and lands at gunpoint by the LTTE, and the Muslims in the east were massacred in their mosques in Kattankudy and Akkaraipattu. Muslims also accounted for roughly a third of the victims of the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 26, 2004, with 13,000 Muslim fatalities in Ampara and Batticaloa Districts alone.

- See Brito, The Mukkuva Law; and McGilvray, Crucible of Conflict, 118–33.

-

See Tambiah, Laws and Customs of the Tamils of Ceylon, 129–32.

- See McGilvray, “Households in Akkaraipattu.”

-

See McGilvray, “Matrilocal Marriage and Women’s Property.”

- See McGilvray and Lawrence, “Dreaming of Dowry.”

-

See McGilvray, “Sri Lankan Muslims between Ethno-Nationalism and the Global Ummah.”

- Unlike in Pakistan and Bangladesh where the Jamaat-i-Islami is an organized political party, in Sri Lanka it is only engaged in Islamic education and charitable works.

-

See Spittel, Far Off Things, 312–21; McGilvray, “Jailani”; and McGilvray, Crucible of Conflict, ch. 9.

- See McGilvray, “Jailani.”

-

See Klem, “Islam, Politics and Violence in Eastern Sri Lanka.”

- For details, see sufimanzil.org.

- Mahinda Rajapaksa served as prime minister from 2004 until his election as president in 2005. He was re-elected to a 6-year term as president in 2010.

- Interview August 8, 2010.

- The mainstream Sufi orders in Sri Lanka include Qadiriya, Rifai, Shaduliya (Shadiliya), and more recently Naqsbandiya.

- I have known Makkattar since 1978, when he was still a schoolteacher. The interviews upon which this article is based took place in 2002, 2005, 2010, 2011, and 2012.

- See Makkattar and Juhais, Hallājiṉ Pōtaṉaikaḷ.

- Some details of Shaykh Ismail and his descendants can be found on the web at http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/%7Elkawgw/gen108.html.

- For details, see www.mufliheen.org

- For examples, see Gough, “Mappila ” ; and Peletz, A Share of the Harvest.

- Precedents of this sort of scholarship include Dube and Kutty, Matriliny and Islam; Kutty, Marriage and Kinship in an Island Society; and Hadler, Muslims and Matriarchs.

Bibliography

Abeyasinghe, T. B. H. “Muslims in Sri Lanka in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.” In Muslims of Sri Lanka: Avenues to Antiquity, edited by M. A. M. Shukri, 129–145. Beruwala, Sri Lanka: Jamiah Naleemia Institute, 1986.

Ameer Ali, A. C. L. “The Genesis of the Muslim Community in Ceylon (Sri Lanka): A Historical Summary.” Asian Studies 19 (1981): 65–82.

Ameer Ali, A. C. L. “Some Aspects of Religio-Economic Precepts and Practices in Islam: A Case Study of the Muslim Community in Ceylon during the Period c. 1800–1915.” Unpublished PhD thesis. Perth: University of Western Australia, 1980.

Arasaratnam, Sinnappah. Ceylon. Englewood, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1964.

Brito, Christopher. The Mukkuva Law, or the Rules of Succession among the Mukkuvars of Ceylon. Colombo: H.D. Gabriel, 1876.

Burnand, Jacob. Memorial Compiled by Mr. Jacob Burnand, Late Chief of Batticaloa, for his Successor, Mr. Johannes Philippus Wambeek. Manuscript of an early nineteenth-century English translation in National Museum Library, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Dutch original in the Sri Lanka National Archives, dated, 1794.

Chitty, Casie. The Ceylon Gazetteer. Ceylon: Cotta Church Mission Press, 1834. Reprint edition New Delhi: Navrang, 1989.

Dale, Stephen F. The Māppiḷas of Malabar, 1498–1922: Islamic Society on the South Asian Frontier. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

Denham, E. B. Ceylon at the Census of 1911. Colombo: H.C. Cottle, Government Printer, 1912. de Graeuwe, Pieter. Memorie van de Heer Pieter Graeuwe aan des zelfs Vervanger de Heer Jan

Blommert gedateered 8 April 1676 [Memorial of Pieter de Graeuwe to his successor Jan Blommert dated 8 April 1676]. V.O.C. 1.04.17, Hoge Regering Batavia. Algemene Rijksarchief, Den Haag, Netherlands.

Dube, Leela. and Kutty, A. R. Matriliny and Islam: Religion and Society in the Laccadives. Delhi: National Publishing House, 1969.

Fanselow, Frank S. “Muslim Society in Tamil Nadu (India): An Historical Perspective.” Journal of the Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs 10, no. 1 (1989): 264–289.

Gough, Kathleen. “Mappila: North Kerala.” In Matrilineal Kinship, edited by David Schneider and Kathleen Gough, 415–442. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961.

Hadler, Jeffrey. Muslims and Matriarchs: Cultural Resilience in Indonesia through Jihad and Colonialism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

Hasbullah, S. H. “Justice for the Dispossessed: The Case of a Forgotten Minority in Sri Lanka’s Ethnic Conflict.” In Sri Lankan Society in an Era of Globalization: Struggling to Create a New Social Order, edited by S. H. Hasbullah, and Barrie M. Morrison. New Delhi: Sage, 2004.

Indrapala, K. “The Role of Peninsular Indian Muslim Trading Communities in the Indian Ocean Trade.” In Muslims of Sri Lanka: Avenues to Antiquity, edited by M. A. M. Shukri, 113–127. Beruwala, Sri Lanka: Jamiah Naleemia Institute, 1986.

Kiribamune, Sirima. “Muslims and the Trade of the Arabian Sea with Special Reference to Sri Lanka from the Birth of Islam to the Fifteenth Century.” In Muslims of Sri Lanka: Avenues to Antiquity, edited by M. A. M. Shukri, 89–112. Beruwala, Sri Lanka: Jamiah Naleemia Institute, 1986.

Klem, Bart. “Islam, Politics and Violence in Eastern Sri Lanka.” Journal of Asian Studies 70, no. 3 (2011): 730–753.

Kutty, A. R. Marriage and Kinship in an Island Society. Delhi: National Publishing House, 1972. Makkattar, al-Qutub as-Shaykh as-Sayyid Kalifatul Hallaj Abdul Majeed Makkattar and M. A. C.

M. Juhais. Hallājiṉ Pōtaṉaikaḷ. ISBN 978-955-53017-0-1. Akkaraipattu: Hallaj Wariyam, 2010. McGilvray, Dennis B. “Arabs, Moors, and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim Ethnicity in Regional Perspective.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 32, no. 2 (1998): 433–483. Reprinted in T. N.

Madan, ed. Muslim Communities of South Asia, 3rd ed., 449–553. Delhi: Manohar, 2001. McGilvray, D. B. Crucible of Conflict: Tamil and Muslim Society on the East Coast of Sri Lanka.

Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. Reprint edition: Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association, 2011.

McGilvray, Dennis B. “Households in Akkaraipattu: Dowry and Domestic Organization among the Matrilineal Tamils and Moors of Sri Lanka.” In Society from the Inside Out: Anthropological Perspectives on the South Asian Household, edited by John N. Gray, and David J. Mearns, 192– 235. New Delhi: Sage, 1989.

McGilvray, Dennis B. “Jailani: A Sufi Shrine in Sri Lanka.” In Lived Islam in South Asia: Adaptation, Accommodation and Conflict, edited by Imtiaz Ahmad and Helmut Reifeld, 273– 289. Delhi: Social Science Press. New York: Berghahn, 2004.

McGilvray, D. B. “Matrilocal Marriage and Women’s Property among the Moors of Sri Lanka.” In

Being Muslim in South Asia: Diversity and Daily Life, edited by Robin Jeffrey, and Ronojoy Sen. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014.

McGilvray, Dennis B. “Sri Lankan Muslims between Ethno-Nationalism and the Global Ummah.”

Nations and Nationalism 17, no. 1 (2011): 45–64.

McGilvray, Dennis B. and Michel Ruth Gamburd, eds. Tsunami Recovery in Sri Lanka: Ethnic and Regional Dimensions. London: Routledge, 2010.

McGilvray, Dennis B. and Lawrence, Patricia. “Dreaming of Dowry: Post-tsunami Housing Strategies in Eastern Sri Lanka.” In Tsunami Recovery in Sri Lanka: Ethnic and Regional Dimensions, edited by Dennis B. McGilvray, and Michele R. Gamburd, 106–124. London: Routledge, 2010.

McGilvray, Dennis B. and Mirak Raheem. Muslim Perspectives on the Sri Lankan Conflict. Policy Studies 41. Washington, DC: East-West Center, 2007.

Neville, Hugh. “The Nâdu Kâdu Record.” The Taprobanian 127–128 (1887): 137–141.

Peletz, Michael G. A Share of the Harvest: Kinship, Property, and Social History among the Malays of Rembau. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Ram, Kalpana. Mukkuvar Women: Gender, Hegemony, and Capitalist Transformation in a South Indian Fishing Community. London: Zed Press, 1991.

Spittel, R. L. Far Off Things. Colombo: Colombo Apothecaries, 1933.

Tambiah, H. W. The Laws and Customs of the Tamils of Ceylon. Colombo: Tamil Cultural Society of Ceylon, 1954.

Thiranagama, Sharika. In My Mother’s House: Civil War in Sri Lanka. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.